Killers of the Flower Moon is an eye-roll but Lily Gladstone still needs to win

The first Indigenous woman to be nominated for a Golden Globe needs to be the first Indigenous woman to win a Golden Globe

The three-and-a-half hour opera that is “Killers of the Flower Moon” was the most-anticipated film in Indian Country this year. To say that Indian Country was frustrated and ambivalent would be an understatement worthy of a Minnesotan declaring, “that’s different.”

Whether it was Osage language consultant Christopher Cote’s early conflicted feelings about the film’s audience, Osage columnist Ruby Hansen Murray’s lament about missed opportunities or a full Indigenous panel evisceration on NPR’s It’s Been a Minute, “Killers of the Flower Moon” was a big sigh in Indian Country. A friend of mine who was even an extra on the set admitted he fell asleep the first time he saw it.

Additionally, my good friend Sam Blackwell felt especially betrayed when I started publishing this Substack again and missed my own opportunity. He texted, “I cannot BELIEVE you made me see Killers of the Flower Moon and then wrote about Battlestar Galactica.”

The movie is long, the story is about two white men who scheme and plot through their own incompetence to get rich by killing Osage women, and it ties up the complex history in a five-minute closing scene using a 1940s murder mystery radio show as the vehicle. There’s a lot to hate about “Killers of the Flower Moon,” and rightly so. Although, I do have to say that the amount of Indigenous fashion and pride that’s been inspired by this movie is what keeps me going whenever I’m faced with what to wear to a fancy event.

But as I tilted my head and squinted at it, I thought it was the perfect indictment of white greed, both in the actual story and in the way it told the story. When faced with choices to do the right thing, every white person chooses to do the wrong thing, whether that’s DiCaprio’s Ernest Burkhart or Martin Scorsese’s directing or Thema Schoonmaker’s editing, they all choose the path of delusion. Burkhart chooses to believe he’s taking care of his family, that he’s loving his wife by “protecting” her from his scheming uncle who will ultimately demand Ernest kill Mollie Kyle and Scorsese believes that humanizing the villains makes the case that we’re all human no matter what.

But the actual history of colonization of the United States isn’t just humans being humans, it’s about choices that are made and choices that are unmade.

Lily Gladstone’s acting range has been on full display over the last few years but most of us know her from her role as Hokti, the imprisoned aunt of one of the deceased Reservations Dogs on the show of the same name. In one of the most powerful scenes of the year in 2022 for Indigenous people, she guided Paulina Alexis’ Willy Jack spiritual contact with their ancestors. And in “Killers of the Flower Moon,” Gladstone is true to the source material and offers her own interpretation of Indigenous women of the time.

At the end of the movie, when justice has been meted out (kind of), Gladstone’s Mollie continues to press her husband on what he injected her with, asking, “Have you told all the truths?”

Any child of Indigenous mothers and grandmothers knows there is no other option when pressed like that but to tell the truth. But DiCaprio’s Burkhart doubles-down on the lie and answers, “Insulin,” before she walks out on him, leaving him to face his consequences. It is the most powerful thing an Indigenous woman can do to her abuser: leave them to face the truth about themselves.

That’s how I feel about this movie, it brings the truth in more ways than one to multiple audiences. White viewers are disquieted, we daresay uncomfortable, with the reality of how Osage people had to suffer at the hands of white people. And Indigenous viewers are left with the reality that our generational trauma and pain are just a mirror or frame for white people to see themselves without having to do the actual work of seeing us or wanting to understand our truths.

It's hard for me to explain to my white friends how collectively I was taught to think as a child. It’s truth that I am an individual walking in a colonized world, but I am also a part of a whole whether I am home or abroad in these United States, I have a people and we have a shared identity, history and future all tied together, willingly and intentionally.

What Lily Gladstone does masterfully is she illustrates how Indigenous women have a candor and poetry about the truth of their existence when they’re among themselves as they discuss the reasons why they tolerate their assassins. She also demonstrate how, when separated from her family by the murder of her sister and the isolation of and poisoning by her husband, she writhes in agony that can be felt across the screen. And when she is returned to health, she gives her would-be killer a final opportunity to tell the truth, to be vulnerable, to be reconciled and when he refuses, she leaves him to his fate.

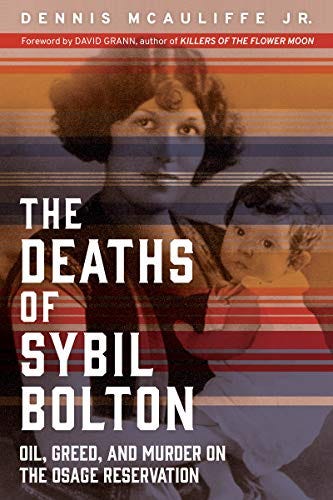

Rolling our eyes at white people trying to tell our story and failing so miserably might give us a headache, but ultimately, we can celebrate the victories for our Osage cousins in bringing light to this history. One of my first journalism mentors Denny McAuliffe wrote about his grandmother in “The Deaths of Sybil Bolton” one of the first (if not the first) books on the subject of the Osage oil murders and it’s now in reprint.

Lily Gladstone’s performance earned a Golden Globe nomination and it’s my deepest hope that not only will she be the first Indigenous woman nominated but also the first Indigenous woman to win a Golden Globe.